When it comes to screenwriting, one of the most important aspects you need to consider is narrative structures.

A narrative structure is an underlying framework that outlines the order and manner in which plot elements are presented. Think about your screenplay structure as a blueprint. It is an overall outline, with a clear beginning, middle, and end, and other important narrative elements.

If you are writing for an emotional effect and want your story to be memorable, it is important to consider enhancing your narrative with different screenwriting structures.

We are presenting the top 5 most well-known screenwriting structures that are commonly used by writers and storytellers when crafting a narrative. These are:

- 3-Act Structure

- The Hero´s Journey

- 8-Sequence Structure

- Dan Harmon’s Story Circle

- Blake Snyder’s Beat Sheet

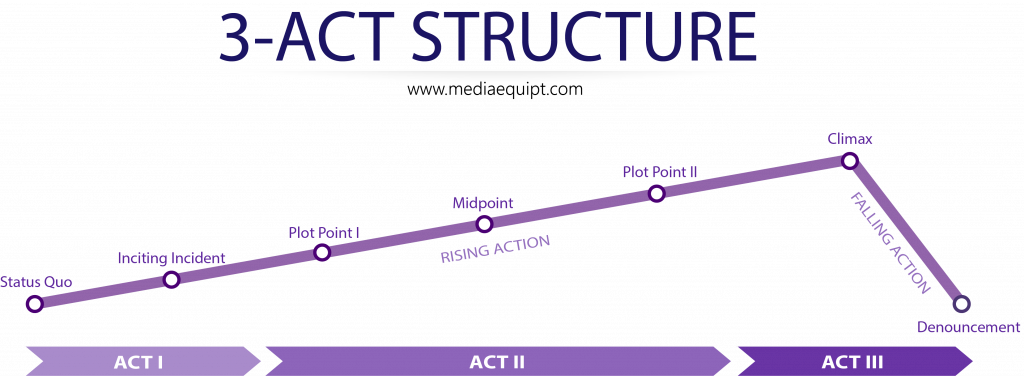

1. The 3 Act Structure

The 3-acts are the most basic of all screenwriting structures. The foundations for Three-Act Structure theory was laid out by an Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath Aristotle (Ἀριστοτέλης). In his work Poetics (which is the earliest surviving work on dramatic theory), Aristotle states that for drama to exist in a narrative, there must be six elements: plot, character, thought, diction, music, and spectacle.

Aristotle also theorized that every story has a clear beginning, middle, and end (a.k.a. Three acts). He proposed that three segments of the story need to be connected by an underlying cause-and-effect principle. These three acts are among the most common screenwriting structures used.

Further, Aristotle has mentioned that all these six dramatic elements need to be arranged in a particular manner. With three acts, however, it was Aelius Donatus and Syd Field, who have elaborated on it later on, and came up with what is now known as Three Act Structure. Often combined with other screenwriting structures, it usually serves as the foundation for most stories.

The three-act structure is a model that divides the story into three parts, often called Exposition, Rising Action, and Resolution.

Act 1 – Exposition

Status Quo

Status quo in Latin means an existing state of affairs or the already-established world. The most important aspect in the exposition segment of your story is the setup of your world and introduction to your protagonist. This is where most of your world-building will take place.

Inciting Incident

In the middle of the first act, an event known as an inciting incident occurs.

The inciting incident, also known as a point of attack, is a catalyst of your story that sets it into motion. This is the moment when your protagonist is finally faced with an obstacle, or a problem, a moment that will officially launch the journey.

Point of attack challenges the usual status quo, showing that it needs change, and encourages the protagonist to embark on the adventure. It enables the central want of the hero, and through suspense and dramatic tension adds urgency.

End of Act 1 – Plot Point 1

The First Act ends with the protagonist finally setting out for an adventure by crossing a point-of-no-return known as Plot Point 1. This narrative element is equally as important as the inciting incident.

Now the stakes for the protagonist rise, and the whole venture usually becomes a matter of life-and-death. There is no return for the status quo to exist as if nothing has happened. The only choice your hero has is to proceed with the adventure.

In traditional Greek Tragedy, Plot Point 1 was usually commemorated by a change of set elements, costumes, and the chorus putting on different masks.

Act 2 – Rising Action

Now your protagonist has officially ventured for the voyage towards the desired goal. On the way there, your hero will encounter many obstacles, and by surpassing them one by one, the hero will gain the strength and skills needed for the final challenge.

The more the protagonist ventures into the unknown, the higher the stakes are, and the more skills your protagonist acquires.

Likewise, throughout the escalating action sequence, the protagonist usually obtains more allies, whether it is a love interest, a friend, or simply somebody willing to help the character achieve their goal; These characters are significant when it comes to the climax of your story.

Midpoint

This is one of the most important events that can take place in your story. Your midpoint is right in the middle of your narrative and is often known as a false victory or a false defeat. Whatever it is, the midpoint is usually followed by an extreme realization.

Midpoint is always a good spot for a plot twist, big battle sequence, or some unexpected event to occur. This narrative element affects how the rest of the story is going to unfold. Midpoint is one of the most challenging testing grounds for your protagonist.

End of Act 2 – Plot Point 2

Time of the crisis, often referred to as Dark Night of the Soul. Everything has collapsed. Your protagonist loses everything, including faith in themselves. This is a perfect time for your protagonist to reflect, see the quest’s true nature, and come up with an unexpected solution.

Thus for your protagonist to transform into something greater, a sacrifice has to be made. Only then, the hero will be able to cross into the third act, being metaphorically reborn and ready to save the day.

Act 3 – Resolution

The final act is usually the shortest one. Events escalate here pretty quickly, leading up to the highest dramatic tension, known as climax. In the third act, the protagonist has to utilize all the acquired skills and bring all the allies to face an antagonist and accomplish the quest.

Climax

After a long journey, this is the part when your story will resolve itself. Your protagonist has the required knowledge and skills to fulfill the need and face the final adversary, also known as the antagonist. Stakes are higher than ever, but conflict resolution finally comes when the antagonist is defeated.

Order is restored, the day is saved, and the hero is accomplished.

Denouement

As the story comes to an end, everything should fall right back to its place. The hero should accomplish the mission, all the loose ends should be tied up, and dramatic tension must be subdued. This is a good part to reflect on the story as a whole and emphasize important themes/lessons that your protagonist has learned.

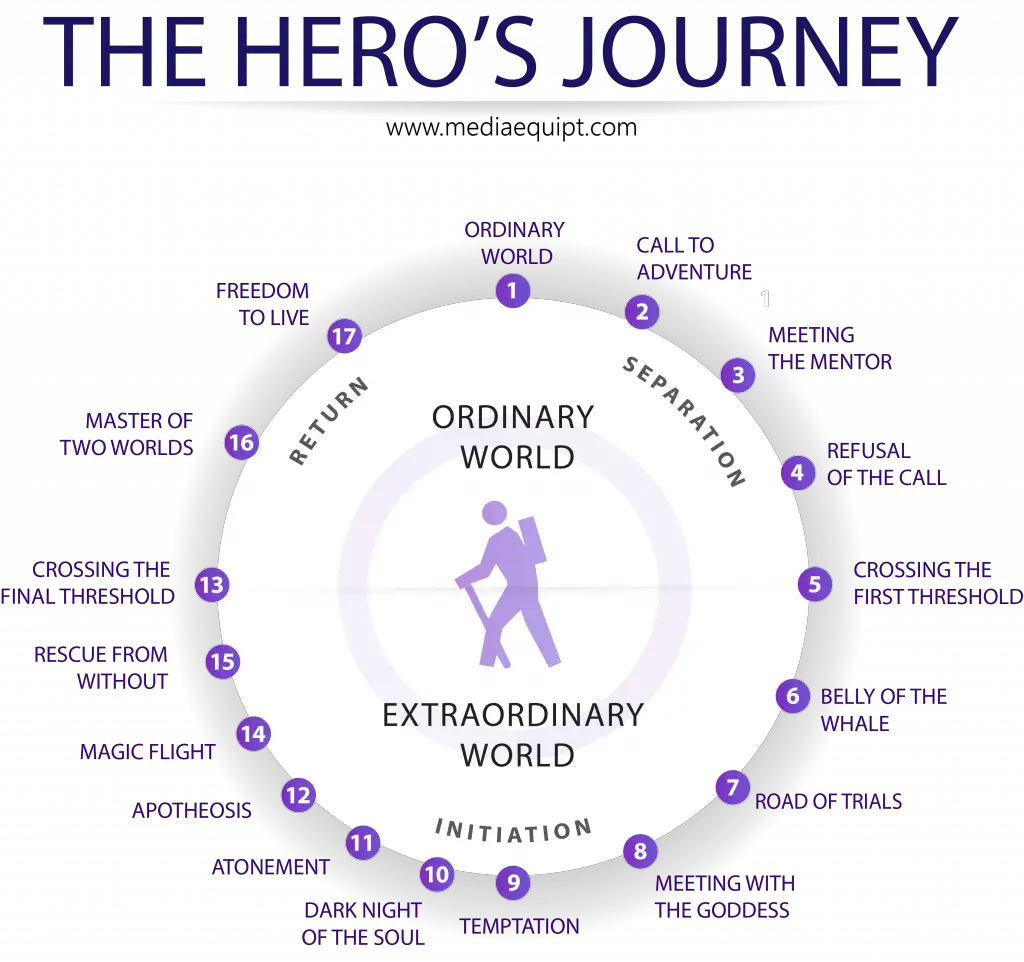

2. The Hero’s Journey

This is one of the most well-known screenwriting structures. The term Hero’s Journey was coined by an American anthropologist and a professor of comparative mythology, Joseph Campbell. Campbell has traveled worldwide, collected fairy tales, studied legends, dissected local mythologies of different cultures, and concluded that all the stories essentially follow a universal pattern known as a monomyth.

Monomyth follows a hero going on an adventure into the realm of the unknown, becoming the master of this world, and returning to the status quo, fulfilled with a completed mission. Similar to the Three-Act-Structure, the monomyth has three sections in which the story is divided. These sections are known as Separation, Initiation, Return.

Campbell was the first theorist to bring mythological/psychological concepts of the known and the unknown (order and chaos) into the storytelling theory. Others followed him in this principle, applying it to all the narrative frameworks.

Separation

Fundamentally, Separation is the First Act of your story. This is when the Hero receives a Call to an Adventure (inciting incident), and with the guidance of a mentor figure, decides to Cross the First Threshold and embark into the realm of chaos.

Here are 5 subsections, of the Separation part of Hero’s Journey:

- The Ordinary World:

- Call to an Adventure

- Refusal of the Call

- Meeting the Mentor

- Crossing the First Threshold

Initiation

For the hero to self-actualize themselves, the protagonist needs to pass through an underground initiation of the world of the unknown. Bypassing the Road of Trials and acquiring new allies, skills, and tools on the way (known as Meeting with the Goddess), the hero loses everything due to their tragic flaw (Temptation). It is only through the period of hardships and self-reflection (Atonement ), the protagonist can fulfill the destiny of the quest (Apotheosis).

Here are 7 subsections that take part in the Initiation of the Hero’s Journey:

- Belly of the Whale

- Road of Trials

- Meeting with the Goddess

- Temptation

- Dark Night of the Soul

- Atonement

- Apotheosis

Return

Now your hero’s journey is complete; the hardest part comes next: to apply the knowledge learned on the quest and return to the ordinary world (Magic Flight). The hero selflessly faces the final challenge in Crossing the Final Threshold and returns to the world of the ordinary, now being a master of the known and the unknown (Master of Two Worlds),

Here are 5 subsections that take part in the Return of the Hero’s Journey:

- Magic Flight

- Rescue from Without

- Crossing the Final Threshold

- Master of Two Worlds

- Freedom to Live

You can learn about Hero’s Journey in more detail in our article Introduction to Hero’s Journey, where we describe each subsection in detail and offer relevant examples in popular movies.

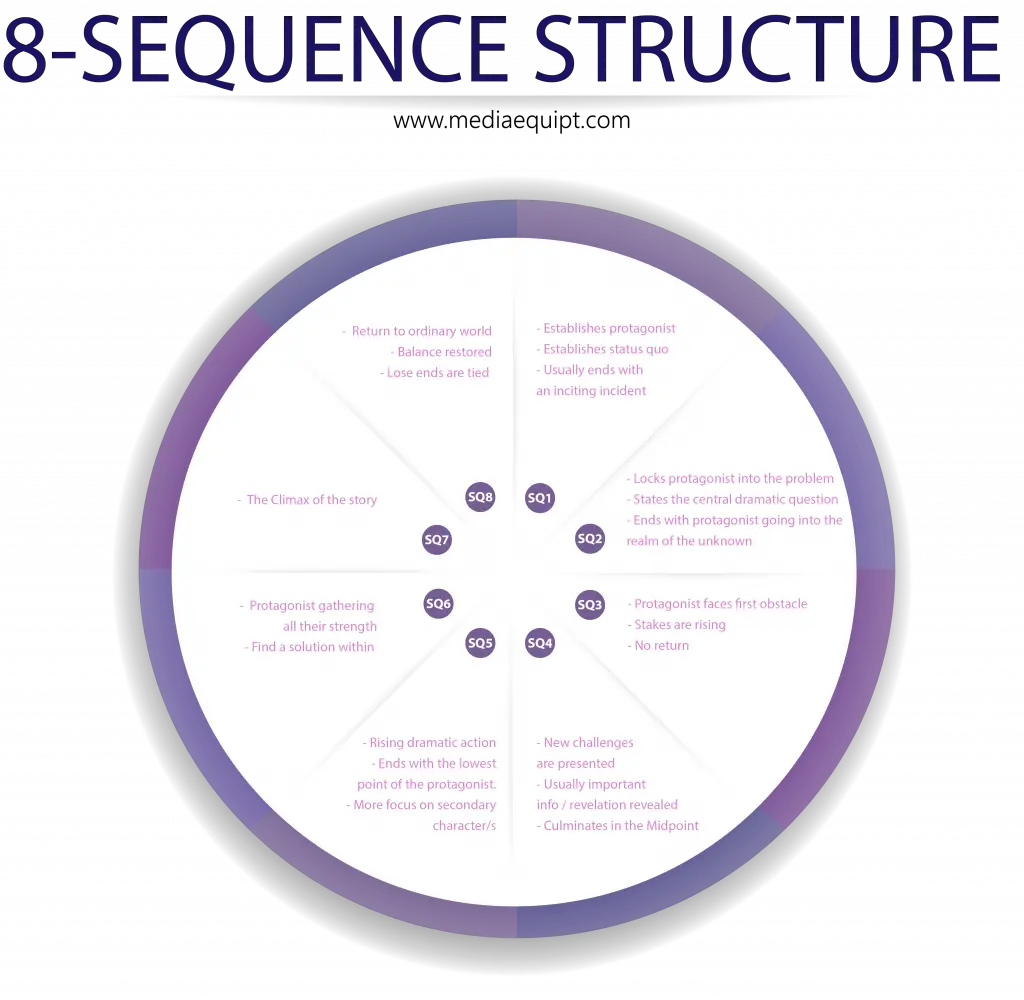

3. 8-Sequence Structure

Eight-Sequence Structure is similar to a 3-Act Structure. The only difference is that within the three acts, it has 8 different sequences.

Sequences 1 and 2 are usually subsections of the First Act. Sequences 3, 4, 5, and 6 are subsections of the Second Act. And Sequences 7 and 8 are subsections of the Third Act.

When working with this structure, it is important to regard each sequence with its beginning, middle, and end. Each sequence should be around 15-pages long (considering that you are working on a 120-page script).

Act 1

Sequence 1:

The first sequence is the exposition aspect of the story that establishes your protagonist, status quo, and usually ends with an inciting incident (sometimes inciting incidents can occur in the second sequence).

The first sequence is usually the hardest one to write since it lays out the foundation for the rest of your story. You must establish your protagonist’s traits, clearly demonstrate the world, and plant the seeds for the central dramatic question in this sequence.

Sequence 2:

The second sequence establishes the predicament of the story. It locks the character into the problem, clearly states the central dramatic question, and sends the character into the realm of the unknown by the end of it.

It is still a good place in your story for exposition and the right time to establish your character’s central want.

The end of sequence two is equivalent to Plot Point 1 in a Three-Act-Structure, or Crossing the First Threshold in the Hero’s Journey framework.

Act 2

Sequence 3

Now that your character has crossed into the Second Act, it is time for them to meet their first obstacle. As your hero attempts to navigate the first challenge, the stakes are rising, and it is clear now that there is no return unless the quest is completed.

This sequence corresponds to the Road of Trials in Hero’s Journey or Fun and Games section in Blake Snyder’s beat sheet.

Sequence 4

The fourth sequence continues presenting new challenges to the protagonist and culminates in a Midpoint of your story. This is usually accompanied by some sense of revelation, important information, or an event that later on changes everything.

Sequence 5

This sequence further emphasizes rising dramatic action and ends with the lowest point of the protagonist. Usually, there is more focus on a secondary character in this sequence. It elaborates on a B-story-line to give the audience a breather before the protagonist reaches the lowest point.

Sequence 6

This is the Dark Night of the Soul moment of your hero. It ends with your main character gathering all their strength and finding a solution within. An inclination to succeed and a final hope is what ultimately helps the hero to overcome this period. The sequence usually ends with a sacrifice that your hero commends.

Act 3

Sequence 7

The story finally reaches its climax in the seventh sequence. This is the ultimate finale of your story, a time for the hero to face the final boss and complete the journey.

Sequence 8

This sequence completes the story. The voyage of the hero is accomplished, and balance is restored to the world of the ordinary. It is important to make sure that all the loose ends are tied here.

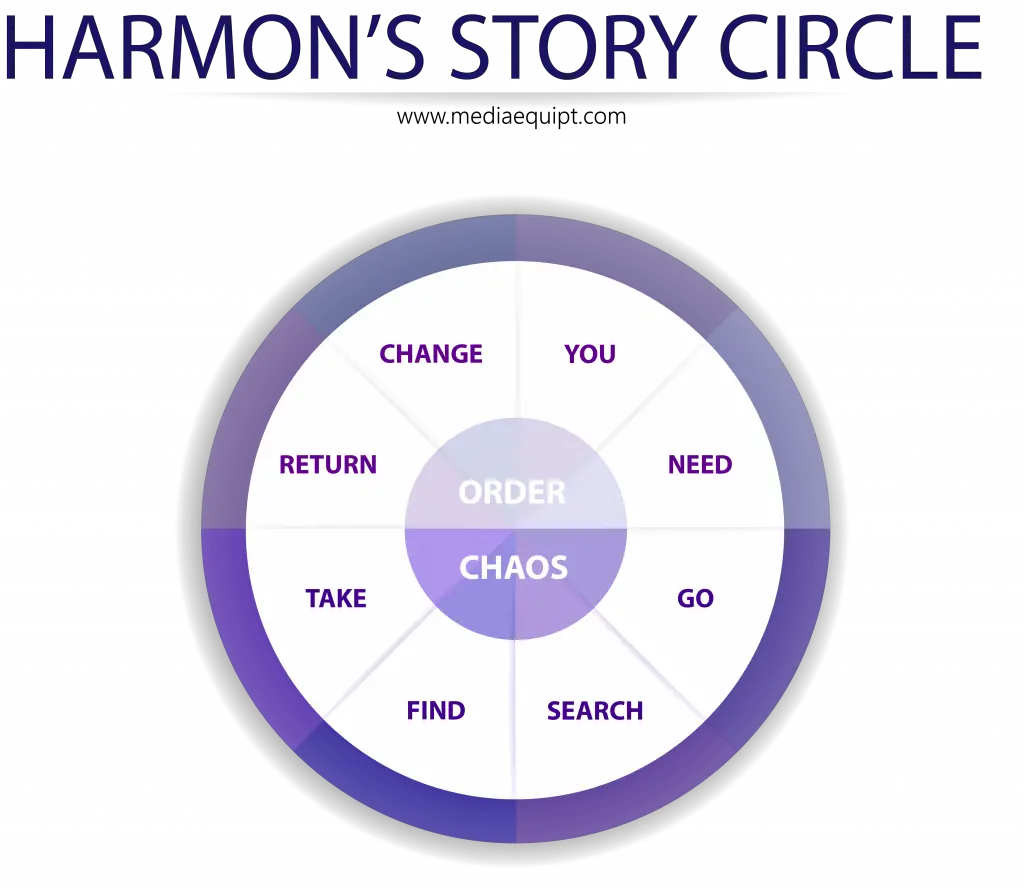

4. Dan Harmon’s Story Circle

Dan Harmon’s Story Circle is essentially Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey but simplified.

It consists of 8 essential steps that every story has to pass through. Story Circle is a good screenwriting framework in terms of structure, but it can also help you devise the character and understand internal and external journeys.

The circle is divided into two halves and 8 sections; the top half of the circle is known as the ordinary world, and the bottom is known as the world of chaos.

The 8 Steps in the Story Circle

1. You

Sets up the protagonist of the story and the status quo of the ordinary world. This segment of the story circle ends with an inciting incident.

2. Need

Establishes the goal, the purpose for the story to set into motion. Out of the 5 screenwriting structures we have presented, Dan Harmon’s Story circle is the only one that included the need as a part of the narrative.

3. Go

An event that sets the story into motion (inciting incident). This is the first section in the bottom half of the circle, meaning that now your protagonist has entered the realm of the unknown.

4. Search

this is the section leading up to the midpoint of your story. It is equivalent to the Road of Trials, Fun, and Games, or Sequence 3 & 4. The search for the desired need has to be active.

5. Find

The midpoint of your story. Perhaps your protagonist has found what made them embark on this journey in the first place? Or your protagonist has changed their mind about the true meaning of the quest. Stakes are leading up to its logical climax.

6. Take

This section implies the fulfillment of the quest, yet to take it, one needs to achieve a sacrifice. You can also see this recurring motif in Hero’s Journey and Blake Snyder’s Beat Sheet screenwriting structures.

7. Return

Your protagonist has fulfilled their purpose. Now it is only a matter of crossing the final threshold and returning to the realm of the status quo. This is where your protagonist is faced with the final challenge, sometimes the most difficult of them all.

8. Change

Now the transformation is applied to the initial You of the story. A full circle has been completed, and your hero has ended where he has started, only now full of wisdom, experience, and a sense of self-accomplishment.

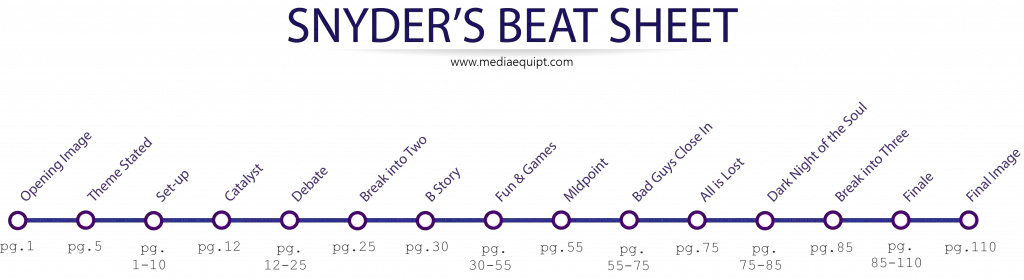

5. Blake Snyder’s Beat Sheet

Blake Snyder was an American screenwriter, consultant, and educator based in Hollywood. He is most well-known for his bestselling book Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need.

In this book, Blake Snyder proposes a story beat cheat sheet that will tell a screenwriter exactly where a narrative device should go. Out of all screenwriting structures on this list, Snyder is the only one who goes as far as giving a particular page number (e.g., Inciting Incident should always take place on page 12), which some writers have dubbed restrictive, while others have praised it as incredibly helpful as it standardizes all the strong scripts to Hollywood conventions. Thus, Beat Sheet can be considered more detailed than other screenwriting structures on this list, as it offers exact page numbers for the different plot points.

This structure works well if one is writing a two-hour feature film, with 110 pages. For 90-minute films, page numbers will differ.

The 15 Story Beats

1. Opening Image (pg. 1)

A strong image that your story begins with. It should not take more than a minute in the screentime, but the first image should immediately bring the viewer into your world, establish aesthetics, genre, and suggest how the story will unfold.

2. Theme Stated (pg. 5)

Blake Snyder suggests stating the theme of your story on page 5 of the screenplay. It is usually done through a secondary character giving your protagonist food for thought regarding the quote that highlights the theme.

While we don’t think that the precise page number matters, it is important to state the theme as early as possible in your screenplay.

3. Set-Up (pg. 1 – 10)

Many established screenwriters suggest that the first 10 pages of your script are the most important ones. The reason for that is that agents and producers only have a limited amount of time to read all the material being sent to them, and they only read the first 10 pages to see whether they are captivated by the story.

The set-up of your story is your exposition, your way to craft the ordinary world and establish character traits in their status quo.

4. Catalyst (pg. 12)

Your inciting incident, your point of attack. The proposed 12th page for this to occur.

5. Debate (pg. 12-25)

The Debate segment of the story is the last chance for the hero to reject the call to an adventure, say this is crazy, and give up. This segment is equivalent to the Refusal of the Call in Campbell’s Hero Journey. This is important to show how dangerous an upcoming adventure actually is and that the hero experiences fear.

6. Break into Two (pg. 25)

Equivalent to Plot Point 1. The hero now actively decides to step into the world of madness and embark on the adventure.

7. B Story (pg. 30)

According to Snyder, a great place to introduce secondary characters with an accompanying storyline is page 30. It provides a writer with a smart cutaway from the central storyline and gives the audience a place to breathe.

8. Fun and Games (pg. 30 – 55)

This is the most exciting part of your story, usually filled with action sequences or at least elaborate attempts by the protagonist to accomplish the goal. This is also one of the hardest to write since it provides space for a writer to be creative and have fun exercising the genre conventions. Snyder suggests for the tone of this section to be lighter than in the rest of the film. However, it is still important to have suspense and raising stakes at hand.

9. Midpoint (pg. 55)

Well, this is the same midpoint as in the three-act structure. Snyder suggests that this is the most important part of your narrative, and from here on, your protagonist either goes up in accomplishing the quest or down. This is when things get dire, and the stakes are up high.

10. Bad Guys Close In (pg. 55-75)

This is the toughest part of writing a screenplay, both for the writer and the protagonist. This is where the victory is jeopardized the most, and the protagonists have the most challenges as the adversaries only grow stronger. This section leads up to the rock bottom of the protagonist’s journey.

11. All is Lost (pg. 75)

This is the opposite of the Midpoint of your narrative; if the midpoint was your False Victory, then this is a false defeat. There is nowhere for Hero to go now, and it is usually when the protagonist is faced with The Whiff of Death. Sometimes it includes secondary characters dying (e.g., Mentor figure), or the protagonist comes in term with their mortality.

12. Dark Night of the Soul (pg. 75-85)

The darkest time for the protagonist, when nothing else matters, yet at the same time, it’s the period of the most powerful transformation. At the end of this segment, the hero regains hope and breaks into the next Act to save the day.

13. Break Into Three (pg. 85)

Equivalent to Plot Point 2, the hero breaks into the third act with a sense of realization and the priorities that are now set straight. The solution to an overall problem is discovered, and both internal and external conflicts are solved.

14. Finale (pg. 85-110)

The hero faces the final obstacle, surpasses their heroic flaw, and restores order and balance. Hero is tested for one last time, and the source of the problem must be dispatched completely for the new world to exist. Ends with a triumph.

15. Final Image (pg. 110)

The final image of your film should be mirroring the opening image of the film. Is the world now changing? Did it remain the same? What does the final image going to leave your audience with?

In Conclusion

As you can see, there is more than one framework to go about structuring your future masterpiece of a script. There is no right or wrong answer to which one you should use; some people prefer a simple Three Act Structure, whereas others like a more detailed blueprint of Blake Snyder’s Beat Sheet.

Sometimes, when you are working on a script, it makes sense to outline your story with two or three proposed screenwriting structures, just to make sure you are avoiding any plot holes or inconsistencies.

The truth is that all of the screenwriting structures essentially follow the same conventions and plot points, yet it is the way they are presented that are different. Having a simple understanding of those 5 narrative frameworks will make your life much easier when it comes to structuring.

However, it is also worth mentioning that rules are meant to be broken. Some of the most talented screenwriters find ways to adhere to those structures yet re-contextualize them or have a fresh new perspective on looking at them.

At the end of the day, powerful storytellers are the ones that find creative ways to retell well-known stories by giving them a new twist. The same applies to screenwriting structures.