Have you ever noticed that all the good stories follow a similar pattern? That there are just certain narrative elements that resonate with many people and have an emotional impact?

While there are a variety of templates used by storytellers, one of the most well-known and influential structures is the Hero’s Journey outline. This story model is profoundly character-centered, as it demonstrates both the internal and external voyage of the hero.

The Hero’s Journey structure is used in films, novels, video games, and all the other types of enterprises where storytelling is required. Understanding its principles will allow you to comprehend the fundamentals of crafting a powerful story.

Our introduction to the Hero’s Journey outline will give you a rudimentary knowledge of this structure, and how with its help you can become a better storyteller.

Who Created the Hero’s Journey?

The term Hero’s Journey was coined by Joseph Campbell in 1987.

Joseph Campbell was an American professor of literature and comparative mythology. He has traveled the world and collected folk tales, myths, legends, and stories from different countries and cultures. Throughout his travels, Campbell observed that all those stories follow a similar pattern.

The pattern involved a hero with a specific goal, traveling into the realm of the unknown, fulfilling the wish through sacrifice, and returning to the world of the ordinary by restoring the balance.

Even though the art of telling a story has existed long before Campbell, he was the one who tailored the term Hero’s Journey and popularized it. According to Campbell, the Hero’s Journey outline is “as old as time” and acts as a guideline to “fundamental human experience”.

Essentially, the Hero’s Journey outline is a story of change and sacrifice; these motifs are present in all the stories. Campbell said that on an elemental level we are all retelling the universal story, over and over again; he dubbed it the monomyth.

The Monomyth: Separation, Initiation, Return

The Monomyth follows a basic yet cardinal structure. It involves a hero, with a particular goal in mind, who needs to venture into the unknown, leaving the ordinary world behind, and return balance for the sake of the greater good through sacrifice.

Another important aspect that needs to be understood, is that Hero’s Journey incorporates a set of archetypal characters. Archetypal character constitutes a patterned quality of a certain character, again present in all stories. Some of the archetypal characters are hero, tyrant, damsel in distress, wise old man, fool, etc.

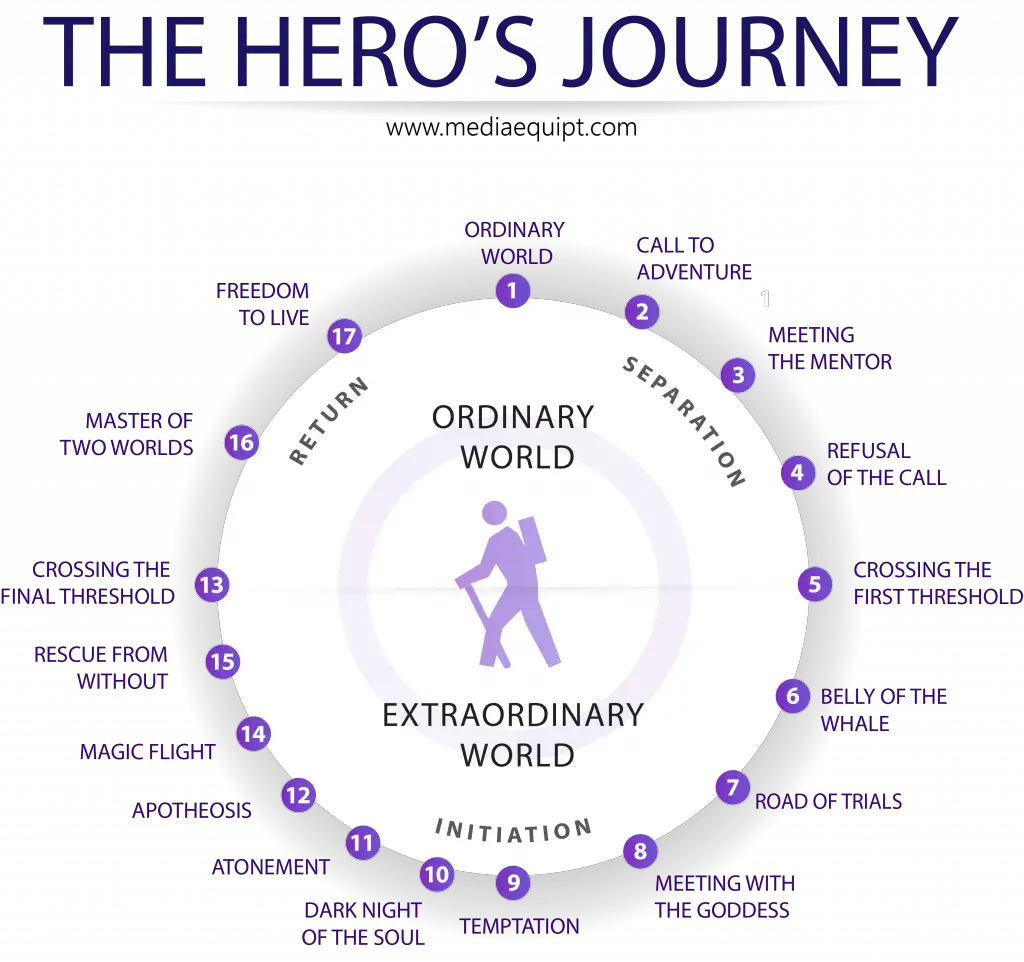

The monomyth is usually depicted through a circle diagram, separated into three segments. In a clockwise direction, a hero needs to pass through the whole circle, and return to the back where he has started from. Only now the hero has manifested his destiny, self-actualized his potential, and completed a sacrifice that is going to bring out the best.

Traditionally, the Hero’s Journey template was divided into three segments and 17 stages. The three segments are separation, initiation, return. We are going to break down these three segments, analyze each stage, and see why each one of them is important for a storytelling purpose.

The Hero’s Journey Outline

Separation

The separation segment represents a departure from the known and the ordinary realm. This is the world that needs some change, needs saving. The hero leaves the comfort of everyday life behind and sails out for the adventure into the unknown territory.

1. The Ordinary World

The Ordinary World is where the hero exists before the story starts, unknowing of what is to come. This is the status quo of our story, an ordinary world that needs to be left behind for the better.

2. Call to an Adventure

This is when the hero is invited to start the journey. This call, also known as an inciting incident, acts as a story catalyst. It disrupts the comfort of the everyday life of our hero and sets him out on an adventure.

3. Refusal of the Call

The moment of doubt before setting out for an adventure. Hero refuses the call, because of insecurities and fears. On a storytelling level, this stage suggests that stakes for the upcoming journey are indeed too high. This is the last moment our hero can quit, but as the risks increase, the hero ends up accepting the call.

4. Meeting the Mentor

Here is where the archetype of Wise Old Man comes in. The mentor figure provides important insight and guidance for the adventure. Usually, the hero is also given an amulet or a tool that will assist them later on in the story. Think about this character for a second. Obi-Wan Kenobi assisting Luke Skywalker with words of wisdom on Tatooine, or Alfred the Butler advising Bruce Wayne. This is also a great part of your story for the exposition. As a writer, you can introduce important information about your world and the story in this section.

5. Crossing the First Threshold

By crossing the first threshold, the hero leaves all that is known and needed behind. This is the moment that marks the commitment of the hero to the journey. It is the point of no turning back, stakes are now higher than ever, and the only way is forward.

Initiation

The initiation segment of the hero journey signifies the world of unknown, chaos, and mystery. Your hero needs to pass these series of tasks, that result in a sacrifice to restore the order from chaos.

6. Belly of the Whale

This is when a hero is faced with his first obstacle. The hero has just entered the world of the unknown as if metaphorically devoured by a whale.

7. Road of Trials

This is where all the fun begins. For the hero to come back to the new reality transformed, initiation must be fulfilled. This is where your hero meets all the obstacles, challenges, and adversaries. During every trial, the hero learns a new skill or gets an insight into how to proceed with the journey.

8. Meeting with the Goddess

This usually signifies the positive union, and where the hero gets united with the allies. This would be a great moment in your story to introduce a love interest or other sidekick characters.

9. Temptation

One of the hardest tasks that a hero must pass through is temptation. This is the moment when the hero is usually offered to join the dark side, to abandon the path.

10. Dark Night of the Soul

That’s where all seemed to be lost. Bad guys are winning. There is no more hope left in the outside world. This is the darkest time of the hero’s journey when the hero loses everything.

11. Atonement

Traditionally Campbell referred to this moment in a story as an Atonement with the Father. Usually, it’s where the hero needs to confront a father figure, god, or some higher perception of Self, to atone all the mistakes. This usually results in the realization that there is still might be hope left. One last chance to make things right.

12. Apotheosis

This is the moment of transformation, realization, and achievement. Apart from in every story when through a sense of revelation the hero achieves the mission of the journey and attains internal bliss. Now the hero is transformed through a metaphorical death, fulfills the goal, and is ready to fight the final battle to return to the world of the ordinary.

Return

The quest is fulfilled, fear is conquered, and the hero feels complete. But what now? In the final segment of Hero’s Journey, the protagonist restores the balance, finds a way to return home, and utilizes all that has been gained during the quest.

13. Magic Flight

Now a self-actualized hero is ready to flee the world of the unknown and bring the elixir of life back to the normal world. This is the escape, the chase before the final battle.

14. Rescue from Without

The same way a mentor figure has helped our hero to cross the threshold into the unknown, the hero needs to receive assistance to return to the ordinary. Whether it is aid from the hero’s new allies, forces of destiny, or a mentor, Hero will require some assistance to return.

15. Crossing the Final Threshold

Hero is ready to encounter the final adversary, confront the biggest fear, and face that final boss. With all the knowledge and experience that the hero has acquired throughout the journey, he is now ready to battle the dragon. This is the ultimate hero moment, a moment where the stakes are at their highest. Whether it is fighting the main villain, accepting a harsh truth, or making the final sacrifice, this is the moment when the hero needs to return to the world of the known.

16. Master of Two Worlds

After completing the journey, now the hero has become the king of the two worlds; the world of known and the world of the unknown. The hero has become what he aspired to be, and the balance is about to be brought.

17. Freedom to Live

Balance has been restored to the ordinary world. Your hero is now wiser and more complete. This is your happy ending when the goal has been fulfilled, and justice has reigned.

The Hero’s Journey Examples in Film

But how can you incorporate monomyth into filmmaking? Have others tried doing that?

Yes! All films follow Hero’s Journey to a certain extent. Remember filmmaking is just another form of storytelling, and thus it’s the monomyth being retold through a cinematic format.

Start Wars: A New Hope

Let’s take Star Wars, and try to roughly interpret it through Hero’s Journey specter.

In A New Hope, young Luke Skywalker sails out on his journey to save princess Lea. As he crosses the known world of his planet, he encounters many adversaries and dangers. Luke makes new allies, follows his mentor, and learns the ways of the Force.

As Luke saves the princess, he realizes that his mission is much bigger than what he thought at first. He now needs to fight Darth Vader, lead the rebellion, and destroy Death Star to restore balance in the universe.

Luke succeeds, risking his own life, and with the help of his allies returns to the ordinary world, now possessing Jedi skills, and knowledge to fight the evil.

Doesn’t the story fit the monomyth structure perfectly? You can see how the creator, George Lucas, was influenced by Hero’s Journey. Lucas has paid tributes to Joseph Cambell and his work in the creation of Star Wars.

Finding Nemo

Let’s see whether this structure works with a different genre. How about a universally loved Pixar animation Finding Nemo?

In an ordinary world of an overprotective clownfish, Marlin is shaken, after his only son Nemo is captured by a pair of Scuba Divers. Marlin’s call to an adventure has left him no choice and has sent him immediately to the world of the unknown, with one universal goal: to locate his missing son.

As Marlin crosses the threshold into the abyss of chaos, he is faced with a serious road of trials: predatory sharks, a pack of jellyfish, evil seagulls. At some point, Marlin enters a stage Belly of the Whale, while swallowed by a giant whale. On his journey, Marlin meets loyal allies: a blue tang Dory, turtles, and Pelican Nigel. With their help, Marlin reaches the final destination, the Dentist’s Office, and finds his son. To retrieve him, Marlin risks his own life, and in the end, finds Nemo.

The story ends with a happy ending, where Marlin and Nemo return home. After being initiated into the world of danger and chaos, Marlin improves his life by recognizing his overprotectiveness and leaves happily ever after with his growing-up-son. Marvin’s journey explores a universal theme of a father-son relationship and utilizes elements of coming-of-age drama; something that many people can emphasize with.

The Matrix

And how about more philosophical films like The Matrix? Did the Wachowskis follow a monomyth structure? Spoiler alert: yes they did.

Neo, a young hacker, leaves his world of the “known” by choosing a red pill; a pill that reveals the truth about the Matrix, and brings him out to the real world. In the real world, where humans are enslaved by Artificial Intelligence, Neo is prophesied to be the One, a man to free humans from the oppression of the machines.

Neo is mentored by his Wise Old Man, Morpheus, and is supported by powerful allies like Trinity. To survive and liberate humanity, Neo fights his enemies, and finally sacrifices his own life.

In the end, Neo indeed becomes the Master of the Two Worlds. e gets resurrected, and masters the laws of the physical Matrix, virtually becoming a superhuman.

Now think about other films. What about Harry Potter, Cinderella, Jaws, Saving Private Ryan, Devil’s Advocate, The Avengers. Isn’t it the same story told in different ways?

As you can see, all great storytellers think alike. These filmmakers used a traditional Monomyth structure, where the hero has completed a conventional journey, yet everyone ended up with such a different movie!

Do not see Hero’s Journey as a creative limitation. Quite the contrary, own in by knowing it, and make it your own!

How to Use Hero’s Journey in Your Story?

So how can you incorporate the Hero’s Journey into your screenplays?

One thing guaranteed: knowing the Hero’s Journey outline can make your storytelling more powerful. Filmmakers ranging from Christopher Nolan to Steven Spielberg have revealed that they use Hero’s Journey constantly in their work.

Remember, a hero’s journey is a combination of not only external but an internal sojourn that your protagonist undertakes. Knowing the Hero’s Journey outline will help you to understand your story on a deeper level.

There are a couple of useful techniques that you can practice to understand this narrative structure better. For example, you can re-watch your favorite film, with the Hero’s Journey outline in front of you. While you watch it, see how well the film fits the pattern. It might skip a couple of stages or re-arrange, but the overall structure will remain the same.

Whenever you are working on the story, try using the beats of your plot to match the beats of the Hero’s Journey. This will give your story shape, structure, and tempo.

And by the way: rules are meant to be broken. Use the general structure of the monomyth to craft the story, but feel free to interchange some things. You should always find creative ways to alter and re-contextualize the hero’s journey wheel somehow. This is what is going to make your work stand out in the end.

In Conclusion

Congratulations! Now you know how all the good stories are made. It is a lot to process, but if you start applying this knowledge when you watch or read something it gets easier.

Knowing the monomyth structure, won’t only make you a better storyteller, but it will make you a better person. If you think about life and its periods, we all pass through our own Hero’s Journey.

Think about growing up. As you mature, you leave the family house and descend into the voyage of the unknown, to transform yourself and manifest a beautiful future. Perhaps the reason why this storytelling structure works so well is that it mirrors our own life.

Further Reading List:

- The Hero With a Thousand Faces (1949) – Joseph Campbell

- The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers (1992) – Christopher Vogel

- Poetics – Aristotle

- Screenplay (1979) – Syd Field